November 284 – Diocletian Becomes Emperor.

“Diocles (Diocletian’s original name form) went on with a brief retelling of what had followed. He ended his harangue, pointing an accusing finger at Aper, with the words ‘He is the murderer.’ Aper reacted with the fury of a wounded lion. ‘He is the murderer, not me,’ he cried out. ‘Are you going to believe the words of a plotter, the words of a filthy son of a slave…’ The last words hit Diocles like a savage lash on the face. For him to be called the son of a slave was the ultimate insult. With a swift motion he drew his sword and plunged it into Aper’s rib cage. . . . Even those battle-hardened men in the ranks froze at the sight of the killing. At that moment, Valerius Maximianus rushed to the top of the knoll and, without giving the men time to recover from the shock, shouted in a booming voice: ‘Romans, this is a moment of destiny. The future of Rome is in the hands of her legions. Hail the Augustus, hail Gaius, Aurelius, Valerius Diocletianus, Dominus, Pontifex, Maximus, Restorer and Protector.’ With these words, he raised high Diocle’s hand still holding unsheathed the bloodstained sword. From below, Galerius repeated the words ‘Hail Augustus Diocletianus…’ The front ranks picked up the chant and in seconds the sounds of cries and the striking of swords and spear on shields rolled like a thunderous wave all the way to the end of the columns. ‘Hail Diocletianus…’ The Roman Empire had a new emperor.” (Kousoulas, 16-17)

“Diocles appeared before the army to swear that he had not killed Numerian. He went on to accuse the emperor’s father-in-law, the praetorian prefect Aper, of conspiring to assassinate Numerian and, according to Historia Augusta, topped off the scene by stabbing Aper to death. ‘My grandfather reported he was among the assembly,’ the writer claims, ‘when Aper was killed by Diocletian’s hand. He used to say Diocletian said, when he struck Aper, ‘Boast, Aper, you fall by great Aeneas’s hand!’ . . . More to the point, Diocles was putting himself in the place of Virgil’s protagonist, the founding hero behind all Roman heroes. Diocles named himself a new founder of Rome, and since Virgil’s praise of Aeneas is always also praise of Augustus, Diocles named himself a new founder of the empire. He agreed with his panegyrists: he was reviving the golden age. . . . For Diocles, the event had a further significance. Years before, a Druid priestess had predicted that he would become emperor only after he killing a boar, and from that time he had searched for a boar on every hunt. Finally, at Nicomedia on November 20, 284, Diocles found his prey, for the name Aper means ‘wild boar.’” (Leithart, 41-42)

Spring 285 – Diocletian Defeated Carinus at the Battle of Margus.

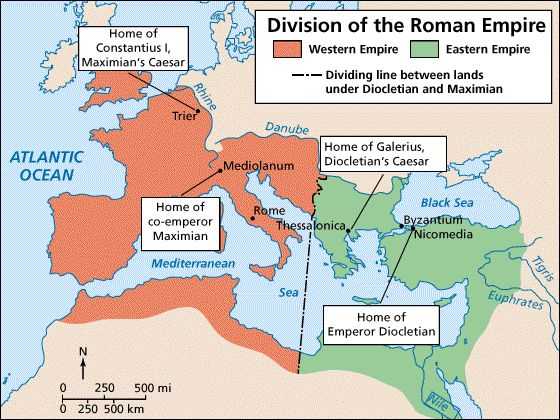

285 – Dyarchy (‘rule of two’) Created. (Maximian Appointed Caesar by Diocletian).

286 – Maximian Appointed Augustus.

287-93 – Carausius ‘Roman Emperor’ in Britain.

288 – Imperial Signa Adopted. (Diocletian Jovius and Maximian Heruclius).

“However, sometime before 289, the Dyarchs launched a new step in the imperial cult when they each took on a signum, Diocletian calling himself ‘Jovius’ and Maximian ‘Herculius.’ When the Tetrarchy came into being in 293, each new Caesar took on his Augustus’ signum too, with Constantius becoming ‘Herculius’ and Galerius ‘Jovius.’ Adoption of a signum was popular practice at the time, at many levels of society, but the emperors were unusual in taking theophoric names – that is, names which conveyed association with gods.” (Rees, 55)

293 – Carausius assassinated and replaced by Allectus.

Tetrarchy (‘rule of four’) created.

1. Diocletian Augustus Jovius

2. Galerius Caesar Jovius

3. Maximian Augustus Herculius

4. Constantius Caesar Herculius

“The Tetrarch’s essential qualifications for office were military. Without exception, they were all successful soldiers, from similar backgrounds in the Balkan lands. A distinguished military reputation had long been a strong card in seeking imperial office, with men such as Augustus, Vespasian and Trajan excellent examples. This was accentuated in the third-century, when no imperial dynasty managed to assert itself, as respect for constitutional procedure evaporated. Senators looked on helplessly as soldier-emperor succeeded soldier-emperor, each new man elevated to power by his army, and in the end most falling victim to assassins or dying in civil war. Meantime, foreign threats were considerable, in particular the Persians on the eastern frontier.” (Rees, 13)

“On his appointment in 293 Constantius forced Carausius back to Britain from his holdings in mainland Europe.” (Rees, 15)

“Soon after his appointment as Caesar in 293 Galerius crushed revolts in the Egyptian cities of Busirus and Coptos, before moving to the Syrian frontier to face Narses.” (Rees, 15)

“Constantine, who in 293 was a young centurion in the imperial guard . . . For the next eleven years Constantine was to remain a member of Diocletian’s ‘sacred retinue,’ traveling with the emperor on his inspection tours and on his military campaigns.” (Kousoulas, 45)

“Constantine was now twenty-two years old (in 293). There is no doubt that he did his share of drinking and whoring around just like his fellow officers. But then he met Minervina and he fell in love. She appears to have been the daughter of a lowly sandal-maker. . . . Because of Constantine’s status, marriage between them was out of the question. . . . But then Minervina became pregnant and Constantine decided to marry her, resorting to the same type of marriage his father had used to marry his mother. History was repeating itself. . . Minervina’s pregnancy was advanced, and in late summer, she gave birth to a beautiful little boy, with dark curly hair. She apparently died at birth. In all the sources, we find no further mention of her, not any reference to a later divorce. She just disappears in the shadows of history. Helena named the little infant Crispus.” (Kousoulas, 53)

294 – Reform of the Mints.

“About the time of the creation of the Tetrarchy, perhaps in 294, the imperial mints were reformed. . . . involved an empire-wide overhaul of the system of coin production, involving both the distribution of mints and the types of denomination. The reform saw mints in most dioceses . . . The reform extended the high-grade bullion content to silver coins; this new argenteus co-existed with the silver-washed nummus, which was retariffed; a copper follies was also introduced, with the uniform legend GENIO POPULI ROMANI (‘To the genius of the Roman people’).” (Rees, 40-41)

New high-grade argenteus silver coin introduced by Diocletian.

“A range of factors might have motivated the hoarding of coins in antiquity, but it is generally assumed that the practice reveals a certain anxiety: in the absence of safe depositaries, an individual might bury his cash holdings in anticipation of war (such as barbarian invasions), civil depredations (such as banditry or unlicensed military requisitioning), an extended absence (such as a journey), or spiraling inflation. In all such cases, it would make sense to hoard high-grade coins in particular, as they would best maintain their value while out of circulation.” (Rees, 41)

“. . . there might be a connection between what appears to have been the continuation of hoarding after the mint reforms of 294 and evidence for ongoing inflation.” (Rees, 41)

295 – Galerius Incites the Manicheans.

“During the days Galerius stayed in Nicomedia, he told Diocletian about the Manicheans, another mystery religion that Mani, a Parthian nobleman born some eighty years ago, had started in Persia. He apparently had a vision that he was the last of the great teachers, after Zoroaster and the Jew that the Christians worshipped as a god. Like the cult of Mithras, the Manicheans, too, claimed that there is a world of light (good) and a world of darkness (evil) and that in the end the light will win out. To Diocletian, another mystery religion would be of little concern. But Galerius told him that the Persian king, Narses, had taken this sect under his wing, had given money to their preachers and sent them to the lands of the Euphrates, and especially to Egypt where they had set up many close-knit communities, with bishops and priests, and teachers and with sacred scriptures they claimed Mani had received from God. . . . There was more. . . . group of ‘select men’ was gathering weapons and that more men were joining the worship of Mani every day. . . . Without delay, Diocletian sent a dispatch to the governor in Egypt ordering him to keep an eye on the Manicheans and report on their activities.” (Kousoulas, 53)

296 – Allectus Defeated by Constantius.

“The Arras Medallion, a magnificent gold piece perhaps minted for distribution amongst the military elite only, offers another grand perspective of the ceremony of adventus. The medallion dates to 296 or 297 and commemorates in a triumphalist tone the reconquest of Britain by Constantius’ army. The highly economical scene is set at a time after the military victory; Constantius on horseback approaches the city of London; the personification of the city greets him from a kneeling position; the legend REDDITOR LUCIS AETERNAE (‘Restorer of the Everlasting Light’) casts Constantius as a savior. . . . The Arras Medallion would no doubt have enjoyed official approval.” (Rees, 48-49)

Gold Arras Medallioin of Constantius’ Victory over Allectus.

297 – Galerius Suffered Reverse Against Persians.

“Galerius campaigned against Persia, but significantly outnumbered in his first engagement, suffered a defeat north of Callinicum in Syria in 297. A tradition built up among later writers that Diocletian shamed Galerius for this defeat by making him walk in front of his carriage.” (Rees, 14)

“Galerius Maximian was unsuccessful in his first battle with Narses . . . Defeated he set off to join Diocletian. When he met him en route he is said to have been received with such insolence by Diocletian that he ran beside Diocletian’s chariot for several miles.” (Rees, 99 quoting Eutropis: Brevarium c. 369)

“Some ancient sources give a graphic but most likely overdrawn description of Galerius’ meeting with Diocletian in Syria upon his return from the campaign. They say that Diocletian had Galerius walk on foot like a slave while he rode his chariot, humiliating his Caesar in front of his men and the local people. . . . In a war council, the senior Augustus asked Galerius to stay in Syria, strengthen his forces with new recruits, train his men and prepare for a more decisive confrontation with the Persians.” (Kousoulas, 62)

“Reports reaching Diocletian in Antioch said that Narses, emboldened by his victory at Callinicum, had begun to use his Manicheans in Egypt to foment unrest in that valuable province. Diocletian decided to deal with the problem in Egypt personally. As an officer in the imperial guard, Constantine marched along.” (Kousoulas, 62)

297-98 – Egypt Rebelled Under Achilleus and Domitius Domitianus.

“Diocletian won a victory over the Carpi on the Danube before himself moving against the usurpers in Egypt in 297.” (Rees, 15)

“Domitius Domitianus’ revolt in Egypt distracted Diocletian from events on the frontier with Persia, the precise dating of which has also proved elusive.” (Rees, 14-15)

“With the Manicheans fighting by their side, the local Greeks and the Egyptian peasants attacked the Roman garrisons which were not strong enough. Within weeks the cities of Coptos, Ptolemais, Busiris, Caranis, and Theadelphia came under the control of the rebels led by Lucius Domitianus who claimed the rank of Augustus. Before long, he even issued his own coins. . . . Other reports said that this Domitianus was only a figurehead and that the real power was in the hands of another man who called himself Achilleus. No matter who the real leader, the rebellion had to be crushed. With a strong force of five legions, Diocletian set for Egypt from Antioch in the late summer of 297. Constantine, a 25-year old tribune in the imperial guard, marched with the rest of the army. . . . The troops passed crossed the desert north of the Red Sea (through the Sinai desert) and entered Egypt. . . . when they came near Alexandria, the largest city in the empire after Rome . . . . Diocletian decided to bypass it and move against the smaller towns. It was a sound strategy. He knew that a siege would take time. . . . With his striking force, Diocletian took one town after another. By the middle of December he had brought his control over most of Egypt and was ready to lay siege to Alexandria.” (Kousoulas, 64)

“Eutropis’ reference to Diocletian’s brutal campaign in Egypt are certainly engaging.” (Rees, 15)

“Considering the duration and importance of this struggle in Egypt, it is curious how little we positively know about the man who for more than nine years successfully defied the Roman power, and whose death in battle deprived his countrymen of their last hope; for it seems probable, though it is nowhere expressly stated, that Achilleus, in spite of his Greek name, was by birth an Egyptian and by religion a Christian. . . . They looked no more to foreign aid, but joined once for all—Greek, Egyptian, Christian, and pagan alike—in one desperate effort for freedom.” (Butcher, 116)

“Then Diocletian came in person with a fresh army . . . Coptos and Busiris, after prolonged sieges by the Emperor in person, were taken and wholly destroyed. Diocletian marched through the Thebaid, and made a treaty with the Nubians and Ethiopians. . . after this Diocletian left Egypt; and with his army the Roman rule was again withdrawn All the Egyptians rallied around Achilleus, who had escaped Diocletian, and Alexandria welcomed him with open arms. . . . The dates of this reign are very difficult to determine, but, as the independence of Egypt is variously computed to have lasted from six to nine years, it cannot have been immediately that Diocletian returned again to reconquer the country. . . . As Achilleus was in Alexandria, Diocletian turned his attention to that city and entered upon a formal siege. He cut off all the aqueducts which supplied the city with water, and being able himself to receive constant supplies and reinforcements by sea. . . Egypt itself was wasted by Diocletian’s former campaign, and deprived of her king, who was shut up in Alexandria. After eight months of brave but hopeless resistance Alexandria was taken by storm and Achilleus put to death. Irritated beyond all self-control at the gallant resistance with which he had met, Diocletian is reported to have sworn that the massacre of the citizens should not cease until their blood flowed to the level of his horse’s knee in the streets. Thousands perished; and the slaughter continued till, . . . Diocletian hailed an opportune stumble of his horse as a sign that the vengeance of Heaven was appeased, and gave orders for the massacre to cease. . . . Diocletian knew how to bide his time, and his full revenge on Egypt was not taken till some years later; but the punishment which immediately followed was heavy enough. Few conspicuous persons in Egypt escaped a sentence of death or exile, the national coinage of Egypt was discontinued. . .” (Butcher, 117-119)

“Diocletian set siege to Achilleus in Alexandria, and after about eight months he defeated and killed him. He exploited his victory harshly; he disfigured all of Egypt with severe proscriptions and slaughter.” (Rees, 99 quoting Eutropius: Breviarium c. 369)

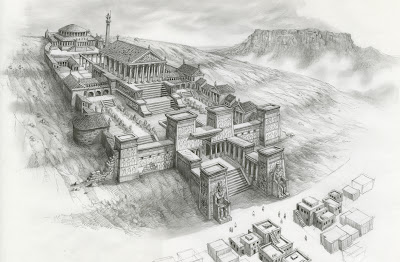

“Early on, Diocletian had sent his heralds under the city walls to proclaim his pledge to spare the lives of everyone, even of the rebel leaders, if the city surrendered peacefully. Achilleus in his reply was as contemptuous as he could be. He used the Greek words ‘Molon lave’—the famous words ‘come and take it if you can’—the Greeks had flaunted at the Persians seven centuries before at the battle of Thermopylae. Angered, Diocletian vowed publicly that when his troops entered Alexandria the slaughter would not stop until the blood reached his horse’s knees. Constantine saw now for the first time how the siege of a great city was carried out. He saw how the catapults and the ballistas breached the walls here and there weakening the city’s defenses and how, in the end, the men had to scale the walls and fight their way through the gaps the siege machines had opened, while powerful rams crushed the gates after consistent pounding, allowing more men to pour into the city. . . . when Diocletian’s forces finally entered the city of Alexandria in the early spring of 298, the slaughter seemed to have no end. Achilleus and Domitianus tried to escape in the confusion but they were captured and executed. After two days of carnage, Diocletian decided to end the violence. . . . Constantine did not return to Nicomedia until late in the summer of the following year. He remained in Egypt with Diocletian. . . . Those who were suspected of disloyalty, and that included many of the Manicheans, were shackled in irons and sent to the salt mines and the stone quarries. . . . Constantine, now a senior tribune in Diocletian’s personal guard followed the emperor down the Nile, all the way to the first cataract and the town of Philae. . . . Diocletian, pleased with what had been accomplished, ordered the construction of an arch in Philae to commemorate his victory and to mark the farthest end of the empire in the land of the Nile.” (Kousoulas, 64-66)

“and worse than all was the loss of their ancient scientific books; for Diocletian, with the superstition of ignorance, conceived the idea that the Egyptians were able by means of alchemy to transmute metals into gold, and that only this could account for the lavish sacrifice of wealth which they had made during these years of struggle for their liberty. He therefore, ordered all such books to be given up to him, and, in spite of the protests and entreaties of the Egyptians, the edict was carried out; and the records of science, which fanciful and faulty as it may have been, was yet the best the world had then to offer on chemistry and kindred subjects, were solemnly burnt by the barbarous Emperor.” (Butcher, 119)

“Those Manicheans who had survived the persecution tried to disappear into the shadows of Egyptian life, hiding their hostility to the Greek and Roman gods and holding to their faith, hoping to survive in obscurity, but Diocletian continued their persecution because he saw them as the agents of the Persian king, . . . In a directive to proconsul Julianus, he ordered that ‘their founders and leaders be subjected to the most severe punishment, burnt in the flames together with their abominable writings. Their followers and especially those who are fanatical shall suffer capital punishment and their goods seized for our fiscus. . . if any officials or persons of rank . . . you shall confiscate their estates and deport them to the salt mines’. . . . The news of the Manichean’s persecution must have given a chill to the Christians in Egypt and elsewhere and must have caused Constantine concern for his mother’s safety.” (Kousoulas, 67-68)

“For nearly three years Egypt remained in suspense, and then the storm broke which left the Church half-dead, and inflicted on the Egyptian nation a blow which it has never recovered.” (Butcher, 120)

“John of Nikius says that in Egypt the persecution began immediately after the suppression of the revolt. This seems much more probable, and would solve some chronological difficulties relating to the Meletian schism in Egypt. In the case also of the Decian persecution we know that it began in Egypt a full year before the publication of the edict through the empire.” (Butcher, 120)

298 – Galerius Defeated Persians.

“However, Galerius augmented his army with reinforcements from the Balkans, and secured immediate gains in Armenia; a crushing victory over Narses was to follow, including capture of the king’s harem. By the spring of 298, Galerius had captured Ctesiphon, deep in the Tigris valley. Narses sued for peace.” (Rees, 14)

“After his success against Narses, Galerius turned to the north where, over the next ten years, he campaigned against the Marcomanni, the Carpi, and the Sarmatians.” (Rees, 15)

299 – Persecution of Christians in Army.

“There is no date given for Lactanius’ dramatic account of the unsatisfactory outcome of the haruspices’ rites which led to Diocletian’s order that all active soldiers perform sacrifice. The suggestion of 299 or 300 makes for an interesting evolution in Diocletian’s policy. This date falls after some martyr acts for Diocletian’s reign: for instance, for his Christian faith, Maximilian preferred death to recruitment in the army in 295; Marcellus renounced his military service in favor of Christ, and was executed in 298. These men were not victims of persecution edicts but of military regulations, but their examples of insurrection might have triggered Diocletian’s anxiety about the presence of Christians in the army. Eusebius states that the persecution began in the army.” (Rees, 60)

“This persecution began with the brethren in the army. . . ” (Rees, 120 quoting Eusebius, History of the Church c. 324)

“Once when he (Diocletian) was involved in the east, he was sacrificing cattle and searching in their innards for portents. At that moment, some of his attendants present at the sacrifice who had knowledge of the lord put the immortal sign on their foreheads; the demons were put to flight by this action, and the rites were disturbed. The haruspices were anxious and they did not see the usual signs in the entrails, and so, as if they had not made offerings, they sacrificed more times. Again and again the sacrificial victims yielded no sign, until Tagis the chief haruspex said, either out of suspicion or insight, that the rites were not responding because profane men were present at the religious ceremony. Wild with anger at this, Diocletian ordered that not only those attending the rites make sacrifice, but even everyone in the palace, and that if they refused they be flogged as punishment; and he instructed that letters be sent to commanders and soldiers be forced to make the unspeakable sacrifices and that those who disobeyed be discharged from service.” (Rees, 107)

“Diocletian was no coward, but the incident in 299 was alarming. Visiting Antioch, he had participated in a sacrifice that failed. Priests slaughtered the animal, and the haruspex, a soothsayer who foretold the future by reading entrails, stepped forward to take the liver from the hands of the servant. Planting the left foot on the ground, he raised his right foot on a stone and bent low to examine the liver. He found none of the usual indicators. They slaughtered another animal, and another. Nothing. Plutarch had written centuries before about the silencing of the oracles, and the same was happening to Diocletian. His recovery of the Pax Romana was, Diocletian believed, the product of a pax deorum, the peace of the gods. Roman sacrifice was at the center of that peace. It was the chief religious act, the act by which Romans communicated and communed with the gods, keeping the gods happy so Romans could be happy? If the gods stopped talking with the emperor, what would happen to Rome? Did the failed sacrifice in Antioch foretell the end of sacrifice? Did it foretell the end of Rome? What had gone wrong? The presiding diviner investigated and concluded that ‘profane persons’ had interrupted the rites, and attention focused on Christians in Diocletian’s court who had made the sign of the cross to ward off demons during the proceedings. Diocletian was outraged and demanded that all members of his court offer sacrifice, a test designed to weed out Christians. Soldiers were required to sacrifice or leave the sacred Roman army. At least the heart of the empire, in the court and in the army, sacrifices would continue without being polluted by Chrisitians. . . . With the purge of Christians, the problem seemed solved. . .” (Leithart, 16-17)

“Diocletian did not have first-hand experience of the strength of Christianity in its heartland – the diocese of the East – until he was there from 296 to 301; and until the Persian war was over, Diocletian needed as many men as possible in the army, so the faith of any one soldier was not a priority until 298.” (Rees, 62)

“Diocletian, who had come back to Antioch from Egypt, received the report of the great victory (Galerius battle against Persia) . . . Diocletian traveled to Nisibis where he received the Persian delegation in person, having Galerius at his side. The victorious Caesar sat a few paces away from Barbaborsus, the defeated Persian general, a giant of a man. It must have been quite a sight. . . . One week after signing of the treaty, he left for Nicomedia. After almost three years, Constantine was about to see again his mother and little boy. Galerius returned to Thessalonika.” (Kosoulas, 69-70)

301 – Currency Reform.

“Much better attested than the currency decree is the Edict of Maximal Prices. This came into force in November-December 301. It was issued by Diocletian, at Antioch or Alexandria or between the two. . . . The Edict begins with a long rhetorical preamble in which the emperors justify the introduction of the measure; it is this moralized rationale which has been cited as evidence of a weak grasp of economics

“lactanius says that the law on [maximal] prices was repealed after it effectively shut the markets and encouraged further inflation.” (Rees, 43-44)

302 – Galerius and Pagan Philosophers Incite the Christians.

“The issue was first raised by Galerius in the summer of 302. The Christians, he argued, were offending all good citizens by treating the traditional gods with contempt. What was even worse and more dangerous was that disrespect to the gods was the first step toward disrespect to the emperor, which in turn was the gateway to treason.” (Kousoulas, 93)

“During the reign of Diocletian, another philosopher, Porphyrios, became a most prominent critic of the Christian faith. . . the Christian’s total rejection of the traditional gods threatened to weaken everything which held the pagan society together.” (Kousoulas, 94)

“And in Nicomedia, Lactanius, a North African professor of Latin rhetoric, rubbed shoulders with the administrator-cum-polemicist Sossianus Hierocles and the philosopher Porphyry. These last two men are often held up as the intellectual architects of a revived attack on Christians, which was so vicious and protracted that it became known as the Great Persecution.” (Stephenson, 104)

“Galerius had effectively planted the first seed. Lactanius blamed Galerius’ mother Romula, a pagan priestess in her native Moesia (today’s Bulgaria), ‘an extremely superstitious woman who worshipped the mountain deities,’ and who was enraged ‘by the contempt the Christians showed to her sacrifices…She incited her son, more superstitious than even herself, to turn against those people.’ Whatever the personal motives or his mother’s influence, Galerius was the man who suggested to Diocletian that the Christians should no longer be allowed to offend the gods by refusing sacrifice. A few extreme and rather unusual cases of defiance in the army fueled Galerius’ arguments and gave them a sense of urgency.” (Kousoulas, 94-95)

“Other officials told the emperor . . . ‘The Christians’ first loyalty.’ They added, ‘is to a crucified Jew they address as Dominus, claiming that he is their Lord and Savior.’ This last argument impressed Diocletian the most.” (Kousoulas, 95-96)

“…Diocletian, still searching for answers, ‘sent a haruspex to the oracle of Apollo at Didyme,’ near the ancient town of Miletus. Constantine himself, was at the court when the reply came and years later he told the story to Eusebius. ‘[The haruspex reported] that Apollo spoke from a deep and gloomy cavern through a medium, and the voice was not human. [The god] declared that the Pious on Earth were preventing him from speaking the truth and that therefore the oracles that issued from his tripod were without value. This is why he hung down his hair in grief, mourning all the evils that will come to men from the loss of his prophetic spirit. Constantine told Eusebius; ‘I heard the senior Augustus asking his advisors: Who were the pious on Earth? And one of the pagan priests replied: ‘The Christians, of course.’ The Christians indeed were the pious or in Greek evseveis in referring to themselves.” (Kousoulas, 97)

“In Antioch in the Autumn of 302 a Christian deacon from Caesarea Maritima named Romanus disrupted the religious observances that preceded court proceedings. Diocletian ordered him gaoled and his tongue removed. He was killed a year later.” (Stephenson, 105)

February 303 – Beginning of the ‘Great Persecution’

“Diocletian made up his mind around the end of January of 303. According to Lactanius, Diocletian consulted the pagan priests “on the most favorable day to launch the projected action.” They suggested the feast of the Terminalia, the 23 of February. That day would be known later, Lactanius wrote, in the words of Vergil (Aeneid IV, 169-170), ille dies primus leti primusque malorum causa fit” (This day was the first cause of death, the first of suffering). (Kousoulas, 99)

“He began on 23, 303. Dates meant everything to Diocletian. February 23 was the festival of Terminalia (Limits). Established by Numa in the distant Roman past, Terminalia was a festival of boundaries. Neighbors would gather at border stones consecrated to Jupiter, offer sacrifice, and share a meal to maintain friendly relations across property boundaries. . . . Terminalia was also part of the public cult, an annual reconsecration of the boundaries that separated the sacred Roman from the profane non-Roman world. As Jupiter’s incarnation on earth, Diocletian was especially charged with guarding the frontiers, maintaining the sacredness of Rome and its empire, and expelling any pollution that might infect it and bring down the wrath of the gods. As the high priest of the empire, he had purged the Manichaean contagion. Now he needed to deal with the Christians, who posed an even more serious threat. The sect of Christianity had grown out of Judaism, but Diocletian was perfectly tolerant of Jewish citizens. They had their own traditions and had the emperor’s permission to check out of the imperial cult. But at least they had the sense to keep to themselves. These Christians were everywhere. They mixed with other Romans in the markets and even at the court and in the army. . . . Rome would be saved by a baptism in blood, a sacrifice of Christian’s blood.” (Leithart, 20-21)

“The first edict of persecution was drawn up on 23 February 303. It was published (in paper form) the following day in Nicomedia, and elsewhere in the weeks and months that followed. . . . that it ordered the razing of churches, the burning of Christian scripture, the loss of judicial rights for defiant Christians, the loss of relevant rights for Christians in high office, and the enslavement of any defiant Christians serving in the imperial household. It seems that pagan sacrifice was used to establish an individual’s faith in the relevant rulings.” (Rees, 62)

“Terminalia festival of 23 February was chosen . . . When it was twilight that day, the prefect came to the church with generals, tribunes and accountants, and beat the doors down; they looked for the image of God, burnt the scriptures they found, granted booty to everyone, caused plunder, fear, panic. . . . In a few hours the highest building was leveled to the ground. The next day an edict was posted warning that people of that religion would be stripped of all rank and status, that they would be subjected to torture, no matter their class or position.” (Rees, 108 quoting Lactanius On the Deaths of the Persecutors c. 315)

“Immediately on the publication of the decree against the churches in Nicomedia, a certain man, not obscure but very highly honoured with distinguished dignities, moved zealously toward God, and inspired by his ardent faith, seized the edict as it was posted openly and publicly, and tore it to pieces as a profane and impious thing; and this was done while two of the emperors were in the same city – the oldest of all, and the one who held the fourth place in the government after him.” (Rees, 120 quoting Eusebius, History of the Church c. 324) (characters in this account are St. George, Diocletian and Galerius)

“I will describe the manner in which one of them ended his life, and leave the readers to infer from his case the sufferings of the others. A certain man was brought forward in the above-mentioned city, before the rulers about whom I have spoken. He was then commanded to sacrifice, but he refused, he was ordered to be stripped and raised high and beaten with rods over his entire body, until, being conquered, he should, even against his will, do what was commanded. But he was unmoved by these sufferings, and his bones were already appearing, they poured vinegar mixed with salt upon the mangled parts of his body. As he scorned these agonies, a gridiron and fire were brought forward. And the remnants of his body, like flesh intended for eating, were placed on the fire, not at once, lest he should die immediately, but a little at a time. . . . But he held his purpose firmly, and gave up his life in victory while the tortures were still going on. Such was the martyrdom of one of the servants of the palace, who was indeed well worthy of his name, for he was called Peter. Such things occurred in Nicomedia at the beginning of the persecution.” (Rees, 120-121 quoting Eusebius, History of the Church c. 324 (characters in this account are Peter, Diocletian and Galerius)

“But Galerius was not content with the rulings of the edict; he prepared to beleaguer Diocletian by other means. To force him to a policy of the cruelest persecution, he had attendants secretly start a fire in the palace, and when part of it had burnt down, the Christians were denounced as public enemies. . . . So he [Diocletian] now began to rage not just against his household staff but against everyone, and first of all he forced his daughter and his wife Prisca to be tainted by making sacrifice. Eunuchs, onetime so powerful, the support for the palace and the emperor himself, were killed; priests and deacons were seized and condemned without proof or confession, then led away with all their dependants. People of both sexes and every age were taken for burning, not individually since they were so great in number, but in groups they were surrounded by flames; with millstones tied to their necks, household staff were drowned in the sea. The persecution fell no less violently to the rest of the population. For judges were sent to temples and tried to force everyone to sacrifice. The prisons were full, unknown forms of tortures were invented . . . altars were put up in council chambers and law-courts so that litigants could sacrifice first and thus plead their case . . . Orders to do the same thing had been sent by letter to Maximian and Constantius . . . Maximian happily obeyed.” (Rees, 108 quoting Lactanius On the Deaths of the Persecutors c. 315)

“A second edict was announced later in 303 which ordered the imprisonment of clergy. This intensification of the campaign against Christians occurred a few months after the initial edict.” (Rees, 63)

“. . . a royal edict directed that the rulers of the churches everywhere should be thrown into prison and bonds. What was to be seen after this exceeds all description. A huge mass were imprisoned in every place; and the prisons everywhere . . . were filled with bishops, presbyters and deacons, . . . so that no room was left for those convicted of crimes. . . . but that those who refused should be harassed by many tortures, how could one tell the number of martyrs in every province, and especially of those in Africa, and Mauritania, and Thebais, and Egypt? From this last country many went into other cities and provinces, and became famous through martyrdom . . . I was present at Tyre myself when these things [martyrdoms] occurred. . . . Such was the conflict of those Egyptians who contended nobly for religion in Tyre. . . . where thousands of men, women, and children, . . . endured various deaths. Some of them after scrapings and rackings and most severe scourging, and countless kinds of other tortures, terrible even to hear of, were committed to the flames; some were drowned in the sea; others offered their heads bravely to those who cut them off; some died under their tortures, and others perished with hunger. Still others were crucified, . . . others yet more cruelly, being nailed to the cross with their heads downward, and being kept alive until they perished on the cross with hunger. . . . In Thebais, sometimes more than ten, at other times more than twenty were put to death. Again not fewer than thirty, then about sixty, and yet again a hundred men with young children and women, were killed in one day, condemned to various and diverse tortures. . . . Some of them were killed with the axe – as in Arabia. The limbs of some were broken – as in Cappadocia. Some, raised on high by the feet, with their heads down, while a gentle fire burned beneath them, were suffocated by the smoke which arose from the burning wood – as in Mesopotamia. Others were mutilated by cutting off their noses and ears and hands, and cutting to pieces the other members and parts of their bodies – as in Alexandria. Why need I revive the memory of those in Antioch who were roasted on grates, not so as to kill them, but so as to subject them to a lingering punishment?..In Pontus, others endured sufferings horrible to hear. Their fingers were pierced with sharp reeds under their nails. Melted lead, bubbling and boiling with the heat, was poured down the backs of others, and they were roasted in the most sensitive parts of the body. Others endured shameful and inhuman and unmentionable tortures on their bowels and private parts – torments which the noble and law-observing judges devised to show their severity, as more honourable manifestations of wisdom. And new tortures were continually invented, as if they were endeavoring, by surpassing one another, to gain prizes in a competition.” (Rees, 121-122 quoting Eusebius, History of the Church c. 324)

Early 304 – Fourth Persecution Edict Published

“In early 304 the fourth Persecution Edict was published, ordering the whole community to sacrifice. There is no record of certificates being issued, as they had been under Decius; instead, the sources seem to imply that performance of sacrifice before official witness was adequate. . . . a controversy about the main instigator of the edict – was it Diocletian, or Galerius? . . . These details could be used to confirm Lactanius’ impression of Galerius as the most zealous persecutor of Christians and a bully of Diocletian; . . . On the other hand, a rigid territoriality in Tetrarchic authority seems not to have been exercised at this stage, and nothing in the sources suggest that Galerius was overreaching his powers as Caesar. It remains quite possible that the fourth edict was sponsored by Diocletian, and that despite his poor health, he and Galerius were co-operating well in 304. . . . This the fourth edict would have been the first to bring the force of law into direct conflict with all ordinary Christians – until this point, the main objects of the persecution had been Christians in the army, and the texts, fabric and leaders of the church, but now entire communities, one by one, were required to perform sacrifice before magistrates or other office holders.” (Rees, 64-65)

May 305 – Diocletian and Maximian Retire from Office

The ‘Second’ Tetrarchy

1. Galerius Augustus

2. Maximinus Daia Caesar

3. Constantius Augustus

4. Severus Caesar

“Eusebius says that in 305 the new Caesar Maximinus Daia enforced the persecution in the east.” (Rees, 66)

“On the other hand, Maximian Herculius was openly wild and uncivilized in character – even the horror of his expression revealed his fierceness. Indulging his own nature, he followed Diocletian in all his more savage measures. But when Diocletian was weakened by age and considered himself unsuitable to manage the empire, he persuaded Maximian Herculius that they should retire to private life and hand over the responsibility of protecting the state to stronger and younger men; his colleague obeyed reluctantly. . . both men exchanged the insignia of imperial office for private dress on the same day – Diocletian at Nicomedia, Maximian Herculius at Milan. They retired, one to Split, the other to Lucania.” (Rees, 100 quoting Eutropius Brevarium c. 369)

“And so, when Constantius and Galerius Armentarius succeded them, Severus and Maximinus Illyrican natives were appointed Caesars; Severus to Italy and Maximinus to the territories which Diocletian Jovius had held. Constantine, whose able and ambitious mind was agitated from childhood on with a desire to rule, could not bear this; for under the pretext of a religious scruple, Galerius was holding him hostage. Having contrived an escape, Constantine reached Britain after he had killed the post-horses he had used on his journey, to frustrate his pursuers. At the same time and place, his father Constantius was near his life’s end. On his death, with all those present urging him, Constantine assumed power. Meanwhile at Rome, the crowd and the praetorian units proclaimed Maxentius emperor.” (Rees, 96 quoting Sextus Aurelius Victor: Book of the Caesars)

“Constantine was kept hostage by Diocletian and Galerius, and fought under them bravely in Asia; after Diocletian and Maximian Herculius resigned power, Constantius asked Galerius to return his son; but Galerius exposed him to many dangers first . . . Then Galerius sent Constantine to his father . . . After a victory against the Picts, his father Constantius died at York, and Constantine was made Caesar with the consent of the troops.” (Rees, 104 quoting Anonymous Valesianus I c. 390)

“Galerius never liked Constantine but knew that Diocletian did, and as long as the old man was at the helm he avoided any show of open hostility to the son of Flavius Constantius. Now that Diocletian had turned over to him the reins of power, Galerius began to search for ways to keep Constantine shackled down in Nicomedia but without causing friction with his fellow Augustus in the West. He feared, not without reason, that if the young man went to join his father, he would sooner or later claim the dignity of a Caesar and disrupt the Tetrarchy. One plan that seemed to serve the purpose of keeping Constantine in the East was to give him a promotion and send him to far away Mesopotamia where he would be under the command of the new Caesar of the Orient, Galerius’ nephew Maximin Daia. As Galerius soon discovered, keeping Constantine out of the way was not such a simple matter. In late July, a special messenger brought to Galerius a letter from Flavius Constantius. The new Augustus of the West was asking his imperial colleague to send his son to Gaul as soon as possible. . . . Galerius procrastinated for several weeks. His reply to Flavius Constantius was evasive, claiming that Constantine still had duties to perform as a senior tribune in the emperor’s personal guard, and that he would certainly be released to leave for Gaul as soon as possible. But then a second, more pressing letter came from Flavius Constantius just before the Ides of September. . . . Lactanius, who often writes more like a modern novelist than an ancient historian, describes Constantine’s escape from Nicomedia in graphic detail:

“Galerius who could no longer hold back, issued marching orders to Constantine in the evening but asked him to not leave until the following day, because he wanted to give him any last minute instructions that might come to mind during the night. He either wanted to keep him under this pretext, or he wanted to send up ahead a letter to Severus, asking him to arrest [Constantine]. Suspicious of Galerius’ intentions, Constantine took advantage of the moment the emperor retired after his supper, and hastened his departure. He set off at full speed, killing the horses in each post as he went ahead. The next day, the emperor who had deliberately prolonged his sleep until noon, called for Constantine but he was told that he had left immediately after supper. Indignation, fury. He ordered that they take the horses at the relay post and go after Constantine to force him to return. When he was told the post no longer had any horses, he could not hold the tears. In any event, after travelling at incredible speed, Constantine reached his father.’” (Kousoulas, 145-147)

Winter 306 – Constantine and Constantius Battle the Picts of Scotland.

“The barbarian tribe of the Picts in the northern part of the British Isles—in today’s Scotland—had launched raids into the south, across the Hadrian wall. . . . Flavius Constantius was determined to stump out this threat once and for all. Now he could count on his son to lift some of the burden from his shoulders. We have no record of the scene. But it is not hard to imagine the moment Flavius Constantius embraced his son. Constantine must have been shaken by his father’s appearance. The emperor was ill. He had aged rapidly since Rome; his once ruddy complexion was pale, his shoulders stooping. Yet, he wanted to lead the expedition against the Picts. . . . At Gesoricum, Constantine met Crocus, a Germanic chieftain who had been for some time a friend of Flavius Constantius and who had his men incorporated into the Roman legions. Constantine and Crocus hit it off well from the very first moment, and their friendship would one day soon help change the course of time. . . . At the war council Flavius Constantius held before the expedition, Constantine proposed a daring plan. The map they had was certainly crude but it did show a deep inlet north of the land of the Picts. Why not sail north with one legion along the coast until they reached the inlet. Then, have the troops land and attack the Picts from the north while the emperor with his forces attacked them from the south. It was an ingenious but also a daring plan. Not one among those present at the council had even been in that region. Besides, the map was old, drawn by Roman cartographers in the early days of the conquest of Britain. What if it was not accurate and there was no inlet at all? Constantine stood his ground and when Crocus offered to join Constantine with his force, the plan was approved. It worked. Caught between the two forces attacking them from north and south, the Picts were cut to pieces. . . . Constantine’s imagination and bravery impressed Crocus and the other officers. Within a few weeks, he had won the respect of seasoned warriors and he had moved out of the shadow of his father. . . . Constantine remained with Crocus in the land of the Picts, to put the agreement into effect and install the garrisons that would keep the peace. . . an urgent message from his father’s Praetorian Prefect. He was asked to come to Eboracum without delay. . . . When, after a wild ride, Constantine arrived with his friend Crocus to Eboracum, he found his faher in bed, gravely ill. . . . Before he died he told Crocus and the senior commanders who had gathered around his deathbed that he wanted Constantine to be his successor. . . . Eusebius, one of Constantine’s most ardent and consistent admirers, writes in his Ecclesiastical History that Flavius Constantius ‘who had not participated in the war [the persecution] against us,’ died ‘happy and thrice-blessed,’ leaving the imperium to his ‘legitimate son, the most wise and pious,’ who was ‘acclaimed Augustus by the legion’ . . . the funeral pyre was erected outside of the walls in an open field where the legions assembled with their officers in an impressive array of uniforms and colorful regalia. . . . As the flames died out—Aurelius Victor tells us—Crocus with the consent of the other commanders called for the elevation of Constantine to Augustus in the place left vacant by the death of his father. Then, the cry of the senior legion commander, ‘Hail Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus Augustus,’ was taken up by the officers and the men in the surrounding hills. The familiar tumult of thousands of swords and spears striking the shields filled the valley. The towns-people joined in, shouting at the top of their lungs, ‘Hail, Augustus.’” (Kousoulas, 149-155)

July 306 – Constantius Died. His Son Constantine Proclaimed Augustus.

“Eusebius also says that in 306 Maximinus Daia issued edicts ordering that individuals be summoned by their registered name to perform sacrifice. This is said to have occurred in Caesarea, Eusebius’ home town.” (Rees, 66)

“Lactanius tells us another new emperor pronounced in 306 – on his father’s death , Constantine’s first act was to restore legal status to Christianity.” (Rees, 66)

309 – Persecution Edict by Maximinus Daia in the East

“There was one further edict of persecution, issued by Maximinus Daia in 309. The command for universal sacrifice was restated, pagan temples were to be reconstructed and pagan high priests appointed.” (Rees, 67)

Spring 311 – Edict of Toleration by Galerius

“Just before his death in spring of 311, Galerius, then the senior Augustus, published an Edict of Toleration. This edict was published on 30 April, and its text is preserved in Latin by Lactanius and in Greek by Eusebius. Both writers claim that Galerius was driven by his worsening physical condition to confess the Christian God. . . there is no evidence of a Christian confession in the text of the edict. . . . Galerius edict is notable for its emphasis on imperial clemency, not contrition, and a rather grudging tone towards Christians.” (Rees, 67-68)

June 313 – Edict of Milan (Granting Full Toleration for all Religions)

“Before Licinius pursued maximinus Daia into the east (where the latter was to die), he published the ‘Edict of Milan,’ on 13 June 313. The edict was in fact a letter, issued at Nicomedia, where Maximinus Daia had been only a month earlier. The edict is issued in the names of Licinius and Constantine, and takes its name from the conference between the two at Milan earlier that year, at which much was discussed, including religious affairs. According to the edict, privileges and property were to be restored to Christians; and religions including Christianity were now to be tolerated unequivocally. The edict thus grants considerably more concessions than Galerius’ Toleration Edict two years earlier and that of Maximinus Daia a month previously.” (Rees, 69-70)

“The Edict of Milan in 313 AD, issued by Constantine, had granted religious tolerance and freedom but Licinius, who was the Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, broke the agreement in 320 AD. He began to persecute Christians, a policy that finally resulted in the civil war of 324 AD. It became a war of religions as Constantine’s army fought under the banner of the labarum against the pagan armies of Licinius. Constantine and his troops emerged as the victors and this is often viewed as the end of the pagan Empire and the beginning of a new Christian era.” (Morgan, 23)

Sources:

Butcher, Edith Louisa. The Story of the Church of Egypt, vol. 1, London: Smith, Elder, & Co., 1897.

Eusebius. The History of the Church from Christ to Constantine, Translated by G.A. Williamson. London: Penguin Books, 1965.

Kousoulas, D.G. The Life and Times of Constantine the Great: The First Christian Emperor. n.p.: BookSurge Publishing, 2007

Leithart, Peter J. Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom, Downers Grove, Il: Intervarsity press, 2010.

Rees, Roger. Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd., 2004.

Stephenson, Paul. Constantine: Roman Emperor, Christian Victor. New York: The Overlook Press, 2010.

Related links:

Timeline compiled by Brett Stortroen; writer of the original novel, Night of the Dragon: The Saga of Saint George.

Hyperinflation and Tyranny in Diocletian’s Roman Tetrarchy

Timeline of Roman Tetrarchy (284-313) by Brett Stortroen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.