Fernando Magellan (Fernão Magalhães – Portuguese) and his brother Diogo were the sons of Rodrigo de Magalhães who had been appointed sheriff to the Port of Aveiro in the northwest coast of Portugal. Due to Rodrigo’s loyal service to King João II, the two young boys were allowed to study as pages at the royal palace in Lisbon. However, their family nobility was only fourth in ranking out of five. The Magellan brothers were indeed fidalgos, but they would never be guaranteed vast wealth or prestige; they would have to earn their livelihoods by hard work and dedication.

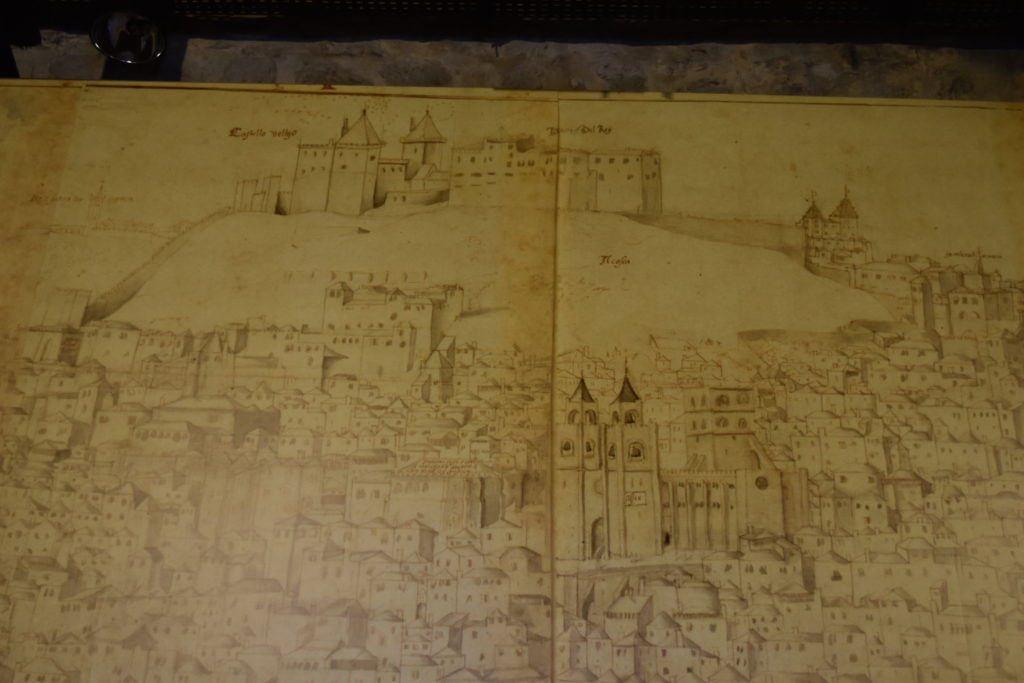

Saint George Castle

In the Alfama district hillside, a steep winding path would have led Magellan upward toward the Royal Palace also known as the alcáçova, built upon the highest peak of Lisbon’s seven main hills. Surrounding the palace were the imposing military towers and high walls of Saint George Castle. It was originally a tenth century Moorish fortification and strategic outpost liberated during the Reconquista.

Due to severe weather, forces headed to the Holy Lands had anchored off the Portuguese coast in the northern city of Porto. These included contingent European knights of a Second Crusader army. It was D. Afonso Henriques—warrior of the Iberian Reconquista and Portugal’s first king—who persuaded these crusaders to join forces and liberate Saint George Castle in Lisbon from the entrenched Moors.

The Royal Palace

During Magellan’s life as an apprentice in the royal palace he would have been tutored in literature, martial skills, mathematics, astronomy, and navigation.

The Royal Ceremonial Hall and Lower Chambers

The royal ceremonial hall was used to entertain guests, hold official councils, and celebrate religious festivals. Visitors, including Magellan at times, would have entered the chambered hall built of stone and mingled in with the king’s inner circle of courtiers. The hall was rectangular with curved pillars supporting the structure along the middle and large windows gave ample illumination. In the winter months, metal fire pits were stationed along the walls and pillars and provided agreeable warmth. Typically, King Manuel would have emerged from a lower chamber stepped entrance and moved along with his royal guards through the chamber greeting courtiers one by one. Later, he would climb some short steps along the perimeter leading to a royal platform overlooking the guests below, then take his seat upon a regal purple throne.

In this setting, Magellan may have met court guests such as the Portuguese playwright, Gil Vicente, who was revered throughout Europe.

The India House

The India House was located near the waterfront. It was first called the Mining House founded by Duarte, the brother of Prince Henry the Navigator. It was the centralized headquarters for Portuguese cartography and navigation. The Mining House also dealt in the trade of Guinea including gold, slaves, horses, iron, and fabrics of many kinds. After trade had expanded with Vasco da Gama’s voyage of 1497–1498 beyond Africa to the west coast of India the Mining House was re-named—the India House. The newly named organization oversaw construction and repairs of ships for naval operations. Items for export were loaded for outgoing missions and imported cargoes were offloaded: pepper, cinnamon, silk, porcelain, silver, and precious stones. With so many returning voyages the India House was a hive of activity. Cartographers and scientists revised naval charts based on new discoveries, modified navigational instruments, and improved astronomical tables. All work was performed under the utmost secrecy.

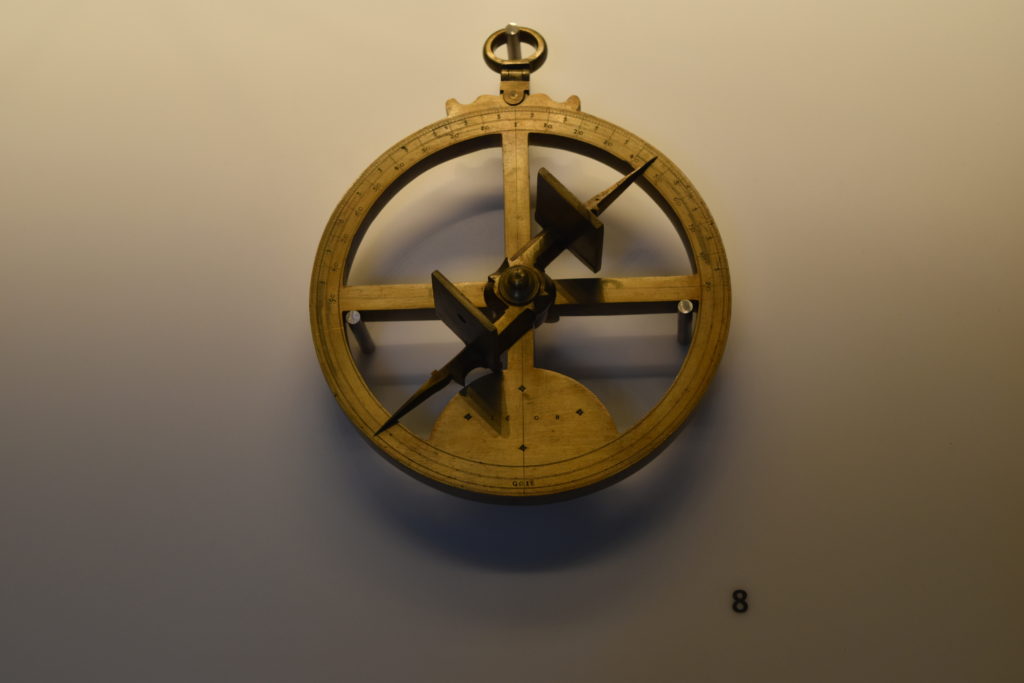

It is quite possible Magellan met famous explorers frequenting the India House during this period, such as Amerigo Vespucci, Martin Behaim, Vasco Da Gama, and many others. New technologies were in development during this period, such as the modified astrolabe, a valuable navigational device.

Ribiera Palace and Palace Square (Praça do Comércio)

The waterfront near the India House had changed much since Magellan had left for India in the spring of 1505. He had returned to Lisbon from his naval service to the crown and had two final appointments with King Manuel in 1515.

Manuel had tired of the original royal palace on the hill. It was too cramped for the ambitious builder, and too far away for him to properly supervise the incoming treasures frequently arriving to port. The new royal edifice was named the Ribiera Palace due to its proximity on the waterfront.

Magellan could have viewed the entire royal complex from a vantage point in the center of the Palace Square (Praça do Comércio). Facing westward, he would see to the left, the Ribiera Palace with its primary facade facing the Tejo River. The ground floor was dedicated as a warehouse, to store cargos of spices and treasures from the returning armadas. It also served as the royal armory. The upper floors contained a royal library, chapel, and grand hall. An imposing crenellated terrace with a fortified bastion was equipped with heavy artillery, and a beautiful hanging garden on a veranda projected outward over the water.

The main palace tower on the far left was connected to the royal residences on the far right by a long multi-storied section in the center. The ground floor of this central structure was an extension of the royal warehouse. The upper floors were long arched loggias with their columns and open views of the Palace Square. One may conjecture they ought to be identified as verandas since they were open on both sides. Following Magellan’s view to the right was the India House on the ground level with three internal courtyards in the rear. The top floors comprised the royal residence quarters which all faced inward to the courtyards. Here, the king looked out his window at the bustling dockyards receiving new cargos and the loading of provisions on new outbound ships.

Magellan would have likely proceeded to his meeting with King Manuel by walking toward a doorway located on the south end of the India House, then a guard examining his appointment document and sending him along with an escort. He would have climbed a stairway, albeit with some difficulty due to his knee wound in Morocco, then walking south toward the palace he would have viewed the galleries of specimens from Africa, India, and the Far East. Proceeding onward he would have climbed another stairway. Its walls were tiled, and most designed with armillary spheres or nature themes. Finally, he would enter the Grand Hall, principally used for receiving dignitaries and crown appointments. Tapestries hung from the walls, many of which depicted famous events and battles of the Portuguese enterprise. At the far end of the hall was the king, seated upon a golden throne with purple cushions atop a two-stepped dais. In his customary style, Manuel would have waved his extraordinarily long arms to conduct an orchestra of musicians with a gathering of courtiers clapping in overtures of feigned applause.

The two appointments between Magellan and King Manuel both ended in clashes of wills. The results would have unexpected ramifications for maritime history.

The Lisbon Cathedral (Sé de Lisboa)

A magnificent structure dominated the city, positioned midway between the royal palace above it and the dockyards on the waterfront below. The Lisbon Cathedral, often called the Sé, was built as both a fortress and sanctuary. Two monolithic towers flanked the entrance and loomed high above the city. It was an edifice built as a product of the Reconquista era. It provided a formidable and strategically positioned frontal base to protect the city during enemy siege.

Magellan embarked on his first voyage in the 7th Portuguese Armada to the Indies in March 1505. His best friend Francisco Serrão and his brother Diogo Magellan accompanied him on the carrack, Botafogo. All three would have attended the solemn send off in the Lisbon Cathedral.

One would expect them dressed in their finest attire, velvet suits of black and purple with white puffy sleeved shirts, and with chins held high, marching toward the cathedral to join the service. It was an architectural wonder and its grandeur heightened by the events about to unfold. Perhaps they marveled at the gothic interior, with light beaming from the rose windows installed in the transept and west façade.

Imagine the following scene in the Lisbon Cathedral:

Captains, pilots, fidalgos, and anyone with rank or command took their seats in the front section of the main chapel. Supernumeraries such as Magellan and those with particularly valued skills took positions in seats near the middle or rear of the main chapel and along the front aisles. Those lowest of status stood in the very rear. The entire cathedral was jammed full. Cool breezes entered through open doors and windows. The archbishop of Lisbon, Martinho da Costa, entered from a side cloister entrance into the circular ambulatory that surrounded the altar of the host. Along the perimeter of the ambulatory were chapels with their tombs adorned above with uniquely sculpted effigies. Many fine works of art, such as the 12 panels painted by Nuno Gonçalves, were displayed in the chapel of St. Vincent located within the Lisbon Cathedral.

Magellan looked above the ambulatory to the gothic-vaulted ceiling and second story windows that emanated radiant light. Clergy went about the sanctuary and lit bowls of incense. The entire room of men bowed their heads in unison and silent confession. After the communion of bread and wine was complete, the archbishop completed the mass.

All eyes now turned to their new commander and viceroy to the Indies, Francisco de Almeida, a war veteran of distinction, who fought in the Battle of Toro and the siege of Granada. From all over the kingdom, men of war, and people of distinction, flocked to join him. They loved him much, as he was perceived to be a man blameless in action, and without any hint of deceit. Almeida was of medium height, a little bald but with a distinguished presence and authority. He raised his head and looked past the altar to the cloister entrance.

King Manuel entered with the king-at-arms carrying the royal standard. They stood near the altar. The banner from the king’s Order of Christ was of white damask emblazoned with a red cross outlined in gold. The king gave a long benediction followed by a moving speech urging his men to perform great deeds and to convert the nations to the teachings of Christ. It was an inspired speech, of great power. Magellan’s eyes watered up. He knew how the king had treated him—but still—the king was speaking with sincere devotion. The king asked all to raise their hands and swear allegiance to the mission and to their Lord. Those seated arose and all made vows of fealty. The king-at-arms then passed the banner to Dom Manuel. Almeida moved from his seat and knelt before the king. A ray of light beamed through one of the second story ambulatory windows. The light mingled with the incense-smoked sanctuary and expanded. As Almeida received the king’s standard the light appeared as a mystical halo. Everyone took notice with great reverence. With the standard in his arms Almeida arose.

Afterward, one by one, commanders and those of distinction knelt before the king and kissed his hand. Finally, Almeida turned from the altar to face the crowd with the banner in his arm.

A herald proclaimed with a booming voice, ‘Dom Francisco de Almeida, governor, viceroy of India for our Lord the King!’ With the announcement great cheers echoed across the chambers.

After the consecration ceremony a solemn procession formed and wound its way down toward the port.

The Jerónimos Monastery

In October 1517, with rejection from the king of Portugal, Magellan departed Lisbon and sailed west on the wide Tejo River to Belém. Looking toward the shoreline, he likely watched construction crews working feverishly upon two great projects.

In the background, a magnificent structure was taking shape. This edifice—The Jerónimos Monastery, had now encompassed the original church of Santa Maria de Belem. King Manuel had purposed it to house his mausoleum. It was to be built in gratitude to God for opening the vast spice trade ushered in by the pioneering voyage of Vasco da Gama to India. The construction had begun in January of 1501. It was financed by taxes levied on the lucrative African and Indian commercial enterprises. The Saint Jerome monks secluded in this great monastery were commissioned to pray for the king’s soul and provide spiritual aid to sailors embarking on new voyages of discovery.

Tower of Belém

In the forefront of the Jerónimos Monastery and a little to the west stood the mighty new Tower of Belém. The work had begun in 1514 and was over half complete. The fortress was constructed upon rocks in the water near the shore. Once completed, it would tower four levels and serve as a formidable deterrent against encroaching enemy fleets.

After the king’s denial for a fleet to discover the Spice Islands, Magellan set off for Spain to seek another king who would listen to his plans. On his departure, he may have watched the early sunlight reflecting off the stronghold’s white stones and the fields along the hills of Lisbon, then embraced the morning, knowing this was surely his last farewell.

Photos by Brett Stortroen

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.